They were called the Forgotten Army. With the war on Britain’s doorstep at an end, those still fighting or suffering in prisoner-of-war camps in the Far East were out of sight and largely out of mind. But for their descendants, the sacrifices made in Burma and beyond live on in the family memory. And over the coming months, two creative projects will bring stories of the campaign to light.

TV adventurer and Parachute Regiment officer Maj Levison Wood has wrapped up filming on The Last Burma Star – a documentary, set for release in November in which he retraces the footsteps of his grandfather, Levison Hopkin Wood, who fought with the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Meanwhile, the family of Peter Kemmis Betty are publishing their father Peter’s memoirs of his three-and-a-half years in Japanese captivity… So many questions For Maj Wood, filming provided an opportunity to visit the places he had previously researched – a process the officer says gave him a much deeper respect for what the Second World War generation endured.

“Seeing the terrain firsthand, learning how little recognition many of these men ever received, and understanding the link between that history and the current crisis in Myanmar – it all brought my grandfather’s story into much sharper focus,” he told Soldier.

“It felt personal in a way I hadn’t expected. My granddad told me quite a few stories when I was young, things he never shared with my dad, his own son.

“Back then, it just wasn’t the norm to talk to your kids about those kinds of experiences. But I think he saw that I was genuinely interested and, because of that, he opened up with me.

“He told me lots of stories about life in the jungle, the leeches, snipers, punji sticks, and booby traps.” A youngster when the war broke out, Hopkin Wood deployed to Burma in the latter stage of the campaign, before serving in Japan until 1947. Maj Wood is grateful that he was able to talk about the chapter with his grandfather, who died when the officer was 19, but still wishes he had asked more.

“You never realise at the time just how valuable those conversations are until it’s too late,” he continued. “I think it’s something a lot of families feel – regret at not having recorded more or pushed a bit further.

“There are so many questions I’d love to ask him now, especially having retraced some of his steps while filming.”

An untold story While those fighting in Burma faced brutal combat and immeasurable challenges, the conflict in the East is also remembered for the suffering endured by Allied prisoners of war held by the Japanese, tens of thousands of whom died through slave labour, malnutrition and disease.

Among those fortunate to come through the ordeal was Peter Kemmis Betty of the 2nd King Edward VII’s Own Goorkha Rifles, whose diary from his time in Singapore’s Changi Prison is now being published.

Called Half a Banana – after his postwar habit of always sharing food – the memoir was edited by his oldest son, ex-cavalry officer Richard. His youngest son, David, is a lieutenant colonel in HQ Field Army. The regular turned full-time reservist explained that although they had read the journal before their father’s death in 2016, as the 80th anniversary of VJ Day approached the family realised they were in possession of a precious piece of history that deserved to be made public.

“It’s a bit of an untold story because a lot of focus of the victory over Japan is on the Burma campaign and the horrors of the railroads,” said Lt Col Kemmis Betty (Scots). “I think the fall of Singapore was such a big shock that a lot of people didn’t want to necessarily talk about it, so the experiences of those that had been in Changi get left out.

“My father counted himself extremely lucky, in hindsight, to have ended up staying in there for the duration.”

Possibly in an act of self-preservation – either to avoid trouble if his notes were discovered or because events were too painful to commit to paper – the diary omits details of deaths at Changi.

Instead, Peter writes of his duties in the camp garden – the produce from which supplemented the inmates’ meagre rations – as well as vital Red Cross parcels and even occasional letters from home. Lt Col Kemmis Betty also explained how the prisoners would maintain morale by playing sports, reading and staging plays or concerts.

“I think they went to great lengths to keep themselves active and not allow themselves to be lazy just doing nothing,” he continued.

“That must have required a huge amount of discipline, but that combination of physical and mental activity kept people going.”

Lessons of war Despite the various distractions, life in Changi was tough. By the end, Peter weighed less than nine stone and lost most of his teeth to malnutrition and lack of care.

After 1945 he stayed in the army and went on to serve in India and later Nepal, as well as fighting in Malaya and Borneo.

But behind his impressive military record, which included a Military Cross and Mention in Dispatches, Peter was an emotional man, deeply affected by his experiences in war.

“He had such deep friendships with the people who’d been through the same sort of stuff as him, either in the Second World War or Malaya and Borneo,” said Lt Col Kemmis Betty.

“There was an amazing bond of comradeship between them all, their families and their children. “Strangely, he had little animosity for the Japanese – and he had an absolute passion for Gurkhas, Nepal and the mountains.

“He was always looking on the bright side of things and loved having fun.” With focus on the European theatre at the time, and even now in moments of remembrance, the officer hopes his father’s story will not only remind modern readers of the sacrifices made in the Far East but provide lessons for those serving today.

“We’re now refocused on war fighting, and I think people should continue to strive to learn from past conflicts, particularly large campaigns and what that would look like were one to happen again, God forbid,” he added.

“There’s the business of comradeship and discipline, and using your talent and ingenuity to keep people going.

“The human spirit can actually put up with a hell of a lot more than you think. It’s about never giving up hope that you are going to get out and everything will be okay eventually.”

Peter was 100 years old when he died and the inevitable passing of the few remaining veterans will remove the last living links to the conflict – likely changing how the nation remembers.

But the threads of inter-generational service remain tightly woven into the fabric of the army. As time takes its course, family legacies such as these will help to ensure history remains part of collective memory and continue to inform those who follow.

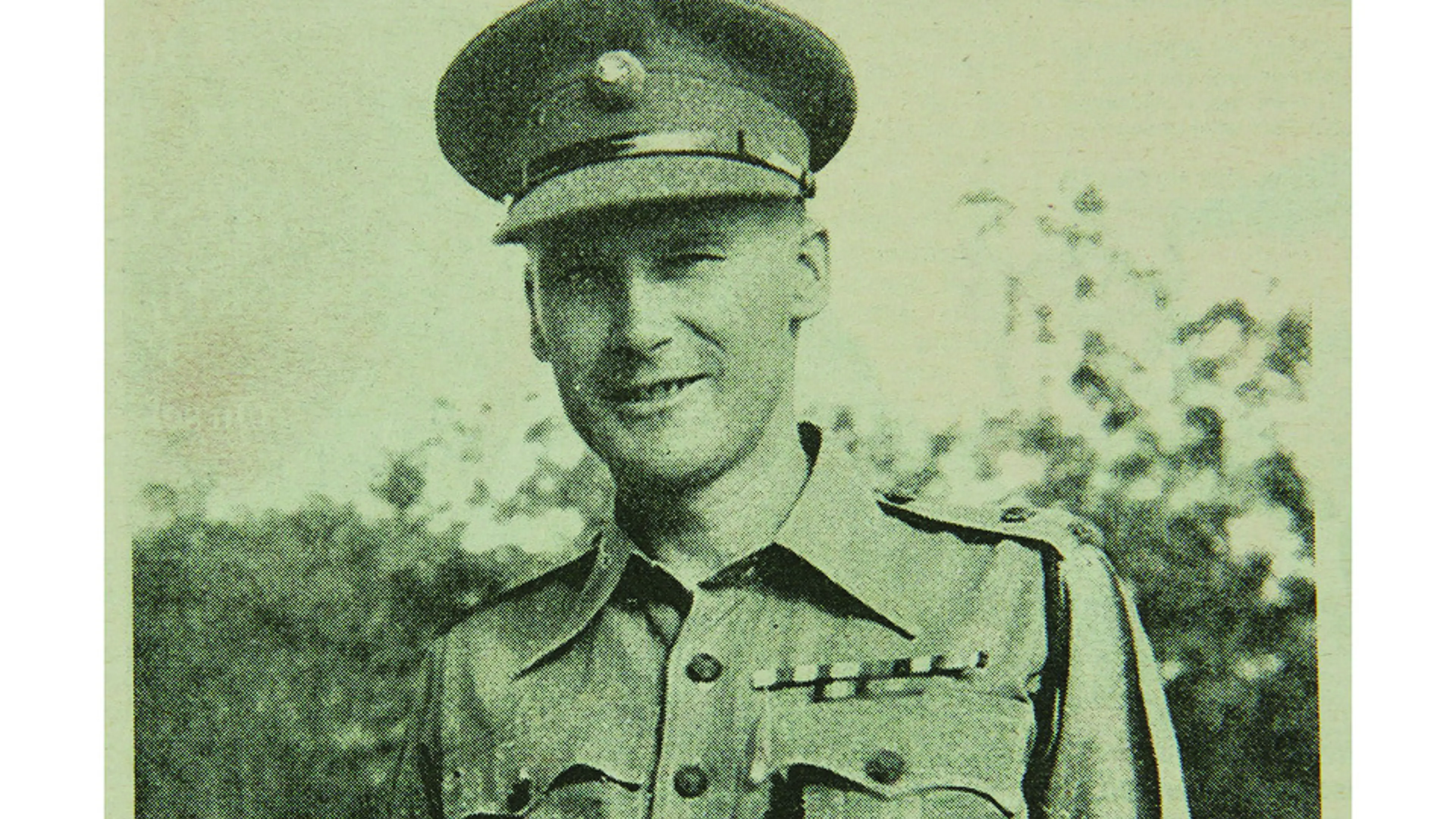

Levison Hopkin Wood

Lt Col David Kemmis Betty