As corporal Paul Robinson stood in modern Berlin recently – 80 years after the Second World War ended – he had a profound sense of the past resonating into the present.

During a tour of the government district – not far from the bunker where Nazi Fuehrer Adolf Hitler finally put a pistol to his head as the fighting raged around – the Royal Engineer could not help but think of today’s generation.

Cpl Robinson

“You can still see the graffiti written on the rubble by Russian soldiers in the Reichstag building,” the NCO, who was on a battlefield study, told Soldier. “They had no idea it would still be here 80 years later.

“Everyone does it and I’ve written my name in Saddam Hussein’s palace in Basra as well as leaving a few scribbles in Afghanistan – you stand and think that the people who liberated Berlin were on the exact spot as I am now.”

For better and worse, the unconditional surrender of the Nazi regime certainly casts an ever-lengthening shadow over the world at large.

The 1940s generation could never have predicted that simmering tensions of the Second World War would reignite in the Balkans 50 years later. Nor could they have foreseen that the Kremlin might one day seek to massage the facts of the “great patriotic conflict” to justify an unprovoked attack on Ukraine.

“Eight decades on we are partners with Germany, Russia are on the other side and there is the potential for another world war,” Cpl Robinson continued.

“History repeats itself and I think if some of the people that died could see where we are now, they would question what their sacrifice was for.

“When you see the pictures of VE Day you can see the relief and joy on people’s faces.

“Some are slumped down smoking a cigarette, exhausted, others are partying with their friends.

“And they will have been reflecting on the mates they lost, too. “They were brothers in arms.

“We owe them what we have today – the world could have been very different if it wasn’t for their courage.”

From the Soldier archive, here are the VE Day memories of some of those veterans

Richard Styan (RA)

Richard Styan

Speaking in 2025, aged 101 Styan, who lives in Yorkshire, experienced some of the fiercest fighting in Europe after landing in Normandy shortly after D-Day. But having served in the 91st Anti-Tank Regiment (Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders) he found himself re-tasked to face the Japanese.

“I do remember VE Day well – back then I was at Hoddom Castle in Scotland, where different units were being prepared to go to fight in Burma. When we were told that the war with Germany was over, everybody just started cheering and clapping. And a few weeks later, when we were docked in India on a troop ship actually bound for the Far East, we heard that the Japanese had given up after the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We were thankful, as fighting them would have meant real trouble. Honestly, the respect for the men alongside whom I served never diminishes, even today. I fought with some extremely skilled and courageous people; they came from all walks of life, taught me a great deal and I shall never forget them.”

Richard Carter (RA)

Speaking in 2015, aged 100 Serving with the Searchlight Regiment, Carter spent most of his war on home soil – targeting attacking German aircraft and V1 flying bombs. It wasn’t until the final 24 hours of the conflict that he actually found himself in Germany.

“I remember VE Day like it was yesterday – I went to Europe on the last day before the war finished. We were out on patrol and word came through that it was all over. I asked, ‘when are we going home?’ but the sergeant said we were off to Japan. We could hear music coming from somewhere and we came across a bandstand. A band was playing beautiful Viennese waltzes, the girls came out and the next minute we were dancing with them. We had been fighting these people for years – yet we’d had so much in common with them really. I was in the Army for five years and nine months and enjoyed it very much – I was in no hurry to join up, but I would not have missed those days for the world.”

Guenter Halm (German Wehrmacht)

Gunter Halm

Speaking in 2015, aged 92 Halm had already achieved fame during the war. Serving at El-Alamein as a 19-year-old anti-tank gunner, he became the youngest recipient of the Knight’s Cross – his country’s highest bravery decoration. Presented with the medal by Fd Marshal Erwin Rommel, he was later captured by the Allies during fighting in Normandy and spent two years as a prisoner of war in the United States.

“I was in a prisoner of war camp in Dermott, Arkansas when the conflict ended. There was no official announcement, but word spread around. We were deeply disappointed; we had hoped until the end that the tide would turn or at least that it could have ended in an agreement between the two sides to cease fire. I was among the first to be transported back to Germany. We found it in ruins. The cities were bombed into the ground and Hildesheim, where I grew up, was just ashes. Today, German troops can march again with their heads held high but to us they say, ‘you old soldiers were criminals’. But we only did our duty for the country. We were called up; those who ran away were stood up against a wall. For us it wasn’t about Hitler’s ideas, it was about comradeship and friendship.”

Victor Gregg (Para)

Speaking in 2020, aged 100 Having already fought in North Africa and Italy, Gregg was captured by the Germans at Arnhem in 1944. He was taken to Dresden where he witnessed the horrific Allied air raid on the city in February 1945, in which 25,000 people died, before escaping captivity. He was picked up by advancing Soviet troops and was with them in Leipzig when news of the surrender broke.

“I had gone on a short walkabout in the city that evening and came in contact with some American PoWs who had this radio that was able to pick up the British World Service. I listened to Churchill’s victory speech, which was a one-in-a-million event. What were my feelings? That’s difficult to answer. It didn’t happen suddenly – everyone knew it was coming. Germany looked like a pile of rubbish that had been tipped out of a bin – thousands of people on the move, all desperately trying to get home, wherever in Europe that might be. By the end of the first week of peace there were feeding centres where civilians were attended to. I have never tried to describe the scenes, simply because I cannot. The overwhelming sense of loss and futility, people struggling against the tide or just hanging on to the nearest queue. It was complete desolation in mind and matter.”

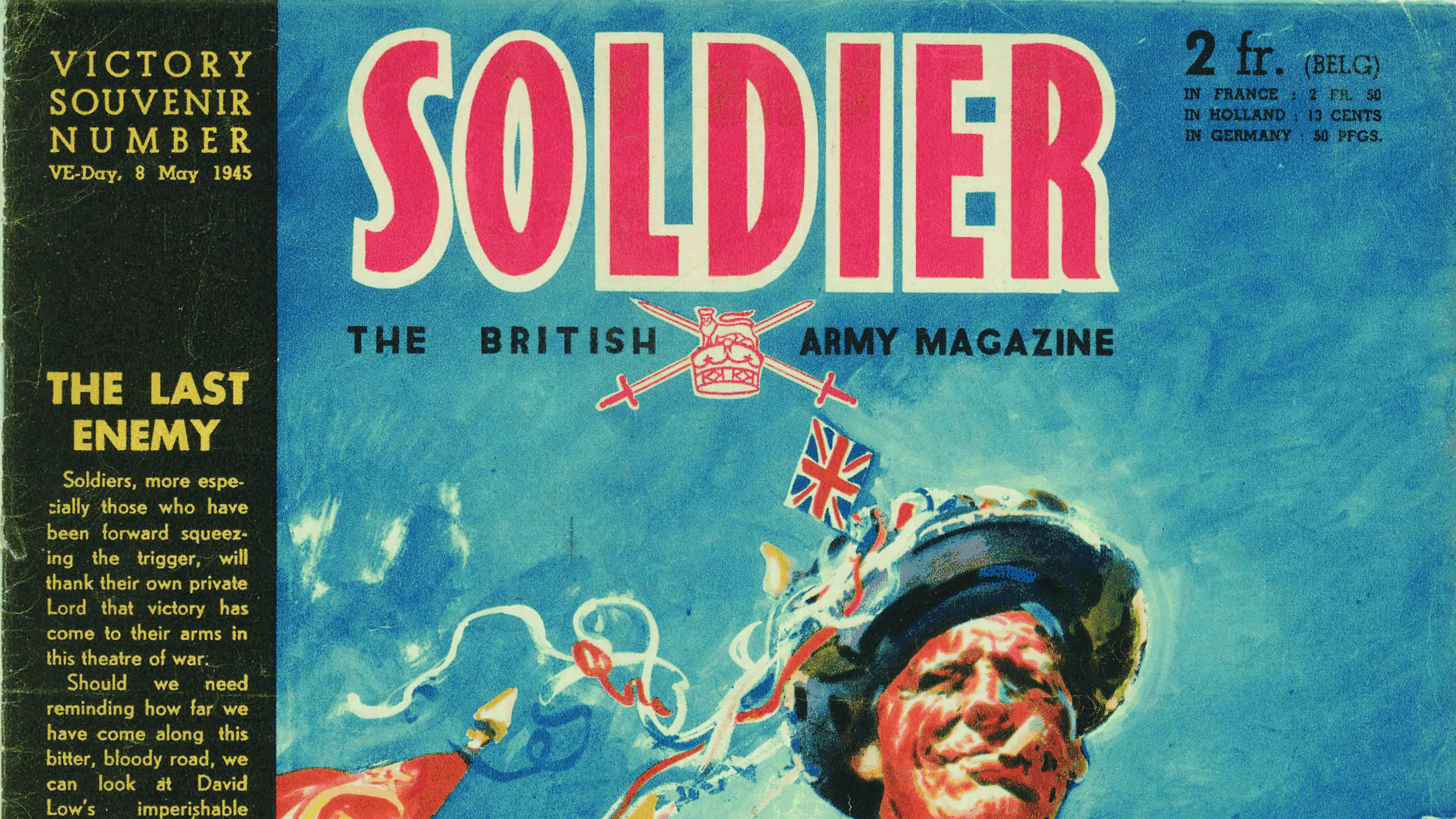

How this magazine was a first-hand witness to the war ending in 1945…

VE Day issue of Soldier magazine

While Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery was receiving the German surrender at Lueneburg Heath, Soldier was at the scene to bear witness to history.

Back in May 1945 Ken Pemberton-Wood was OC of No 1 British Army News Unit – of which this magazine was a part.

Working in the tent next door as Admiral Karl Doenitz discussed capitulation with his British counterpart, the issue to which he contributed (shown above) was a landmark piece of journalism.

Despite being at the epicentre of history, however, he did not recall any huge drama at the time.

“It was all very low key as we did not expect the surrender to stick,” the Royal Artillery veteran, who went on to serve the mag for 33 years, becoming its advertisement boss, said in an interview in 1995. “We were in the news business and weren’t surprised at anything that came our way,” he later added.

“I remember the roads filled with thousands of German prisoners, all very depressed and flinging their rifles onto dumps.”

His team’s achievement was extraordinary. The May 1945, VE Day issue of Soldier remains an important historical document to this day. As well as background features on the conflict, it includes a round-up of reflections from troops fighting through Europe to Berlin. Among those included is George Smith, a tobacco cutterturned-Royal Army Service Corps driver.

He was in a DUKW amphibious vehicle during the D-Day landings and was later wounded in battle.

“I remember thinking as the day went on and boats kept swarming ashore – they’ll never push our lads out now,” he said.

Then there is LCpl Charlie Baker of the Corps of Military Police, who fought at Arnhem.

“Jerry plastered us with shells and mortars,” the NCO recalls. “But though I was there nearly ten days, all I got was shrapnel in my legs.”

And Sjt Andrew Imrie was in the first Buffalo amphibious armoured vehicle to touch down on the east bank of the Rhine as the war entered the final phase.

“I remember how quiet it was – uncanny – and I know I wasn’t the only one to mumble a little prayer,” the junior NCO, who was serving with The Black Watch, told the magazine.

“The boys got their first objective, a communications trench, and within ten minutes there was a stream of prisoners.”

Among other stories in the issue are features on horrific Nazi atrocities, including those committed at the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. Extraordinarily, there is also a poem by Nobel Prize for Literature nominee Edmund Blunden – himself a First World War veteran and friend of writer Siegfried Sassoon.

The work – simply called VE Day – pays tribute to the collective effort, the sacrifice and values for which troops had fought. And it rests as a fitting tribute to their generation: “The life for which they marched and sailed and flew – reunion, restoration, freedom deep and true."